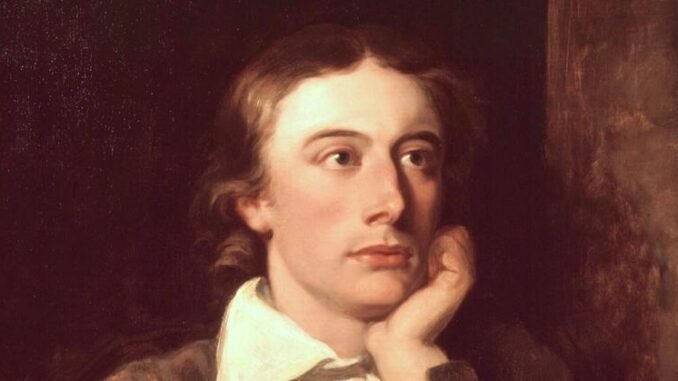

During his lifetime, John Keats was far from the most important poet of the Romantic movement. In fact, he had only been serious about poetry for six years, and the few volumes of his that were published received deeply unfavorable reviews. By the time of his death in 1821, aged 25, he was certain that his work was destined for oblivion. Fortunately, Keats was wrong.

Keats’ childhood

John Keats was born in London on October 31, 1795 into a dark romantic lifestyle. When he was eight, his father died after falling from a horse, and as the eldest of four children, Keats did his best to care for his younger siblings when their mother died of consumption six years later, in 1810. On his mother’s death, Keats’ maternal grandmother appointed two men, Richard Abbey and John Rowland Sandell, as guardians of the family.

Abbey briefly convinced Keats to pursue a career in medicine, apprenticed to an apothecary and surgeon at age 15, but he preferred reading the classics and mythology. He found medicine too horrible for his temperament, and although he received his apothecary’s license in 1816, he abandoned the medical profession shortly thereafter. Financially it was a bad move, blood or not: he should have been given £800 from his grandfather’s trust when he turned 21, but likely due to poor guardianship from Abbey he never saw it. Thanks to his mother, he had some money to share with his brothers, but it wasn’t enough to give him the privilege of writing poetry all day.

The New Romantics

In 1816, Keats’s sonnet “O Solitude” was published in The Examiner, boosting his confidence that this poetry thing might work out after all. He left for the seaside town of Margate to write with his friend, Charles Cowden Clarke, and returned to London with the manuscript of Poems . The collection was a critical failure and an even worse financial disaster, but it earned Keats admission to the “new school of poetry” alongside Percy Shelley and John Hamilton Reynolds.

Today, Keats, Shelley and Lord Byron are all lumped together in a group like the Romantics, but at the time, Keats was a laggard within the group. Byron actually hated Keats’ work as much as the critics did, referring to it as “onanism” in the paper. Shelley had a soft spot for the poet and tried to impart some wisdom to her young friend, but Keats would not listen. Rather than wait until he had a more substantial collection of poetry, as Shelley advised, Keats moved forward with Endymion ., a 4,000-line erotic novel based on a Greek myth written entirely in iambic pentameter that received the worst reviews of the young poet’s career. The critical response was so harsh that Shelley considered publishing a favorable review out of sheer pity. Keats never recovered from the humiliation, and almost gave up poetry altogether, but he later went to Wentworth Place.